Popular Truisms Concerning Memory and Learning - some background

Getting students to remember what we teach them has been a

challenge for instructional designers, teachers, and mentors since time began.

The whole issue is bound up in the in the science or art of memory. In this

blog, I look at a couple of the more widely quoted philosophies of information

retention.

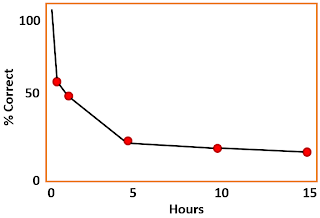

Ebbinghaus and the Forgetting Curve

Ever since Hermann Ebbinghaus published Memory: A

Contribution to Experimental Psychology (Ebbinghaus, 1885) we have felt able to put a factor on how quickly

people forget. The Forgetting Curve

diagram, which is essentially based on Ebbinghaus’ study of his own ability to

remember, indicates that people forget new information rapidly after they first

learn it. This study remained the de

facto standard for the best part of a century and is still found across the

Internet. There are some fairly basic criticisms of Ebbinghaus’ research methodology,

with the obvious one being that his analysis was of himself only—a pretty small

test group and one that does not allow for scientific distance. A second, and

arguably more telling shortcoming of the research is the fact that he chose to

try to remember random letter patterns, which had no meaning or relevance to

him, beyond the test itself. Ebbinghaus knew the letters of the alphabet, but

the letter patterns had no significance which means that he would be unable to

identify patterns, such as words.

This can be seen as a uniquely abstract approach but, when

we extrapolate the findings to the real world, it becomes difficult to use as

an effective baseline; it is seldom, if ever, the case that we teach something

where the students have no previous experience or even terms of reference for

the subject matter. By definition, the random, meaningless letter patterns had

no relevance to the learner.

The Forgetting Curve Diagram

This, perhaps, explains the almost frightening speed with

which Ebbinghaus forgot over 50% of what he had “learned”; a matter of minutes.

It has also led to some educationalists to declare that only through constant

revision of content is it possible to hold back the Canutesque tide of

forgetfulness.

The Learning Pyramid

More widely quoted than the Forgetting Curve, based on a

quick Google search, is the Learning Pyramid. This has become something of an

urban myth in education and training. It is cited as originating from the

National Training Laboratories (NTL) for Applied Behavioral Science, but search

their site and there is not even a reference to it. The popular tale is that

the research from the 1950s has been lost. No matter. The pyramid proposes that

different learning experiences or styles engender different levels of knowledge

retention, as shown in the diagram. Students only remember 5% of what they hear

in a lecture, 10% of something that they read, and so forth.

The Learning Pyramid

The empirical value of the Learning Pyramid has been

questioned—more realistically, discredited—in a number of papers and articles

available on the Web, such as Will Thalheimer’s blog Learning Pyramid Debunked (Thalheimer,

2006). I won’t jump on the bandwagon here, but my instinct is to doubt any

statistical research that delivers such rounded numbers for a study of a

function as complex and nuanced as memory. It appears to be an effort to

categorise study options against Edgar Dale's Cone of Experience (Dale, 1946)

in an easy to use format; a rule-of-thumb, if you like.

So where does this leave the instructional designer?

With these two popular standards in instructional design called into question, how can we have any hope of helping our students to remember what we teach them? The answer may be by looking at elements of these two, rather than assuming that a study or image that appears across the Internet must be accurate in its entirety.

The beauty of both the Forgetting Curve and the Learning

Pyramid is that they are intuitively correct in two areas:

- Memory Fades. Can you remember all of the information that you have ever known? Unless you have an eidetic memory, the answer is no.

- Practice Makes Perfect. If you take a car engine apart you will have more experience of taking a car engine apart than someone who hasn’t.

The problem is that since these two statements are so

obviously true, that we treat both the curve and the pyramid as truisms.

Both theories ignore the complexity of the brain and the

neurological differences between people. It is also the case that both of these

studies assume no, or unrealistically limited, prior experience; Ebbinghaus

knew the alphabet but the random nature of the letters meant that this had no

bearing on what he was memorising, while the learning curve assumes that only

one means of study is used in a learning event. In his defence (not that he

needs me to defend him) Ebbinghaus meant this to be the case, but it is very

unlikely that you will ever design a course for, or teach, a student who has no

understanding of, or even context for, the subject that they are studying. More

strikingly, the idea that the best way to learn about successfully dismantling and

reassembling an engine is by giving a completely inexperienced person a car and

a socket set is laughable (disassembly is easy, putting it back together in

working order is the trick). I am sure that anyone who has done any (successful)

work on their own car began by doing so under the guidance with someone who had

car maintenance experience or by getting hold of a manual; I fondly remember my

first Haynes.

If you want to look at some practical solutions to the

memory challenge, have a look at my next blog on How Do We Ensure That Students Remember What We Teach Them? (Part 2 of 3)

.

No comments:

Post a Comment